Timeline of Final Words

The historical record contains numerous accounts of final statements. Examining them chronologically reveals evolving attitudes toward death, justice, and the power of speech. The following case studies highlight the diverse circumstances and historical challenges associated with famous last words.

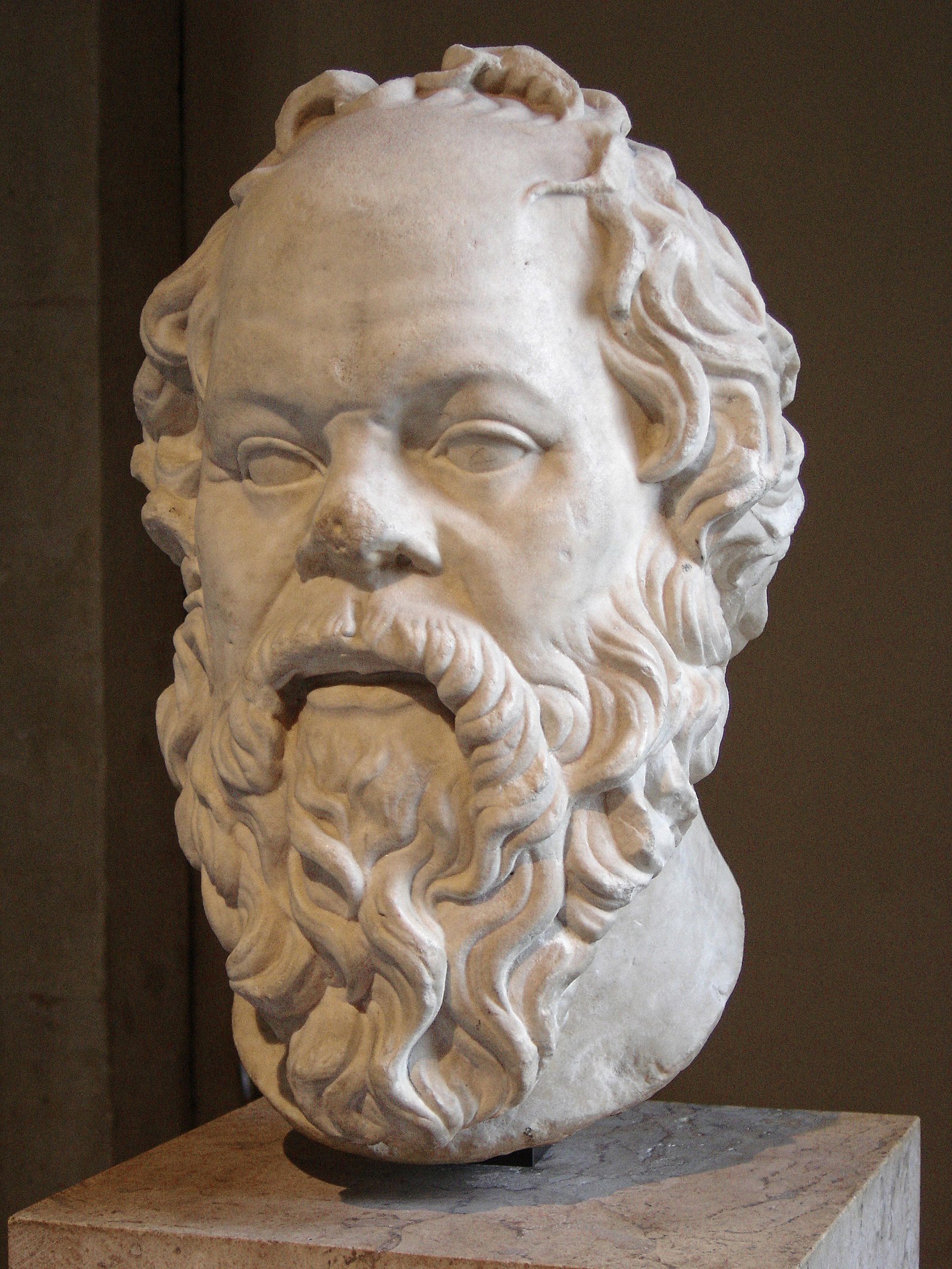

Socrates (399 BCE)

The philosopher Socrates was condemned to death by an Athenian court on charges of impiety and corrupting the youth. His death was not a violent, sudden event but a deliberate, legally mandated poisoning. The mechanism of his death was the Athenian judicial system, and his final hours are among the most thoroughly documented in ancient history, primarily through the writings of his student, Plato, in the dialogue titled Phaedo.

According to Plato’s account, Socrates spent his final day in prison surrounded by his friends, engaging in a calm philosophical discussion about the immortality of the soul. When the time came, he was given a cup of hemlock, a potent poison. He drank it without hesitation. As the numbness spread through his body, he spoke his last words, addressed to his friend Crito: “Crito, we owe a rooster to Asclepius. Please, don’t forget to pay the debt.”

These words have been subject to extensive analysis. Asclepius was the Greek god of healing and medicine. A common practice was to offer a sacrifice, such as a rooster, to the god upon being cured of an illness. Socrates’ statement is widely interpreted as a philosophical claim: that death itself was the cure for the “sickness” of life. His words were not a plea or a lament but a final, ironic affirmation of his worldview. Because they were recorded by a devoted follower in a detailed narrative, they are considered one of the more reliably documented last words from the ancient world.

Julius Caesar (44 BCE)

The assassination of Julius Caesar on the Ides of March is one of history’s most pivotal political disasters. As a dictator who had subverted the traditions of the Roman Republic, he was targeted by a group of senators who hoped to restore the old system. The cause of his death was a conspiracy, and the mechanism was a violent breakdown of political order inside the Senate house itself.

The most famous last words attributed to Caesar are “Et tu, Brute?” (“You too, Brutus?”). This line, immortalized by William Shakespeare in his play Julius Caesar, suggests a final, personal betrayal by his friend Marcus Junius Brutus. However, this phrase is not found in any contemporary Roman historical accounts. It is a dramatic invention, powerful in its emotional impact but historically apocryphal. The term apocryphal refers to a story or statement of doubtful authenticity, although it may be widely circulated as being true.

The primary historical sources offer a different picture. The Roman historian Suetonius, writing over a century later but using earlier sources, reported that Caesar said nothing at all after the initial blow. Instead, upon seeing Brutus among the assassins, he pulled his toga over his head and resigned himself to his fate. Suetonius does note a rumor that Caesar may have spoken a phrase in Greek, “Kai su, teknon?” which translates to “You too, my child?” This has a similar sentiment to Shakespeare’s line but lacks the same definitive, dramatic quality. The case of Julius Caesar is a crucial lesson in how literary narratives can overshadow and replace historical records in public memory. What were Julius Caesar’s last words? The most historically sound answer is that he likely said nothing.

Marie Antoinette (1793)

Queen Marie Antoinette of France was executed by guillotine on October 16, 1793, during the Reign of Terror of the French Revolution. Her death was the result of a formal judicial mechanism—a trial and conviction by the Revolutionary Tribunal. The event was a highly public spectacle, designed to demonstrate the power of the new republic and the definitive end of the monarchy.

Stripped of her finery and transported to the scaffold in an open cart, her final moments were witnessed by a large, hostile crowd. Much of her life had been subject to public scrutiny and criticism, and her death was no different. Yet her reported last words were not a grand political statement or a plea for her life. As she climbed the steps of the scaffold, she accidentally stepped on the foot of her executioner, Charles-Henri Sanson.

Her final, documented words were a simple, polite apology: “Pardonnez-moi, monsieur. Je ne l’ai pas fait exprès.” (“Pardon me, sir. I did not do it on purpose.”) This statement, mundane and human, stands in stark contrast to the political drama of the moment. It reveals not a hated symbol of aristocratic excess, but a person maintaining a basic code of etiquette even at the moment of death. The account is considered reliable, as it was recorded in the private diaries of the executioner, who was a meticulous record-keeper of the proceedings. It provides a poignant glimpse into the person behind the political caricature.

Abraham Lincoln (1865)

The assassination of U.S. President Abraham Lincoln on April 14, 1865, was a national disaster that occurred just days after the end of the American Civil War. The cause was a gunshot wound inflicted by John Wilkes Booth, and the mechanism was a security failure at a public venue, Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C.

Lincoln’s death is a clear example of how famous last words are sometimes invented to fill a historical void. After being shot, Lincoln was carried across the street to a boarding house, where he remained in a coma for approximately nine hours before dying the next morning. He never regained consciousness and therefore spoke no final words. The historical record is clear on this point, confirmed by the multiple physicians and officials who attended his deathbed.

Despite this, several popular myths have arisen. One persistent story claims that Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, upon Lincoln’s death, stated, “Now he belongs to the ages.” While this line is widely quoted, its authenticity is debated by historians; some accounts claim he said, “Now he belongs to the angels.” Regardless of what Stanton said, the key point is that Lincoln himself was silent. The desire for a poignant or meaningful final statement often leads to the creation of narratives that satisfy a public need for closure, even when they are not factually accurate.

Carl Panzram (1930)

The final words of executed criminals offer a different perspective, often reflecting defiance, remorse, or a final commentary on the justice system. Carl Panzram was an American serial killer, rapist, and arsonist executed by hanging at Leavenworth Federal Penitentiary in Kansas on September 5, 1930. His case provides a stark example of final words as an act of ultimate resistance.

Panzram was unrepentant for his crimes throughout his trial and imprisonment. His final moments were consistent with his life’s persona. As the executioner prepared the noose, Panzram reportedly became impatient with the process. His last words were directed at the hangman: “Hurry it up, you Hoosier bastard! I could kill a dozen men while you’re fooling around!”

These words, recorded by witnesses including the prison warden, are a chilling expression of his violent character. They are not words of reflection or apology but of contempt for the authority that was ending his life. The final words of executed criminals are a significant category of historical statements because they are spoken within a formal, documented state procedure. They offer a raw, often unsettling insight into the psychology of individuals and the finality of capital punishment.