Causes & Mechanisms of Airport Delays

Airport delays are rarely caused by a single, isolated event. Instead, they are the product of a complex system of interlocking factors where one problem often exacerbates another. Understanding these mechanisms is crucial to grasping why certain airports consistently underperform. The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) categorizes delays to track their origins, providing insight into the system’s primary points of failure.

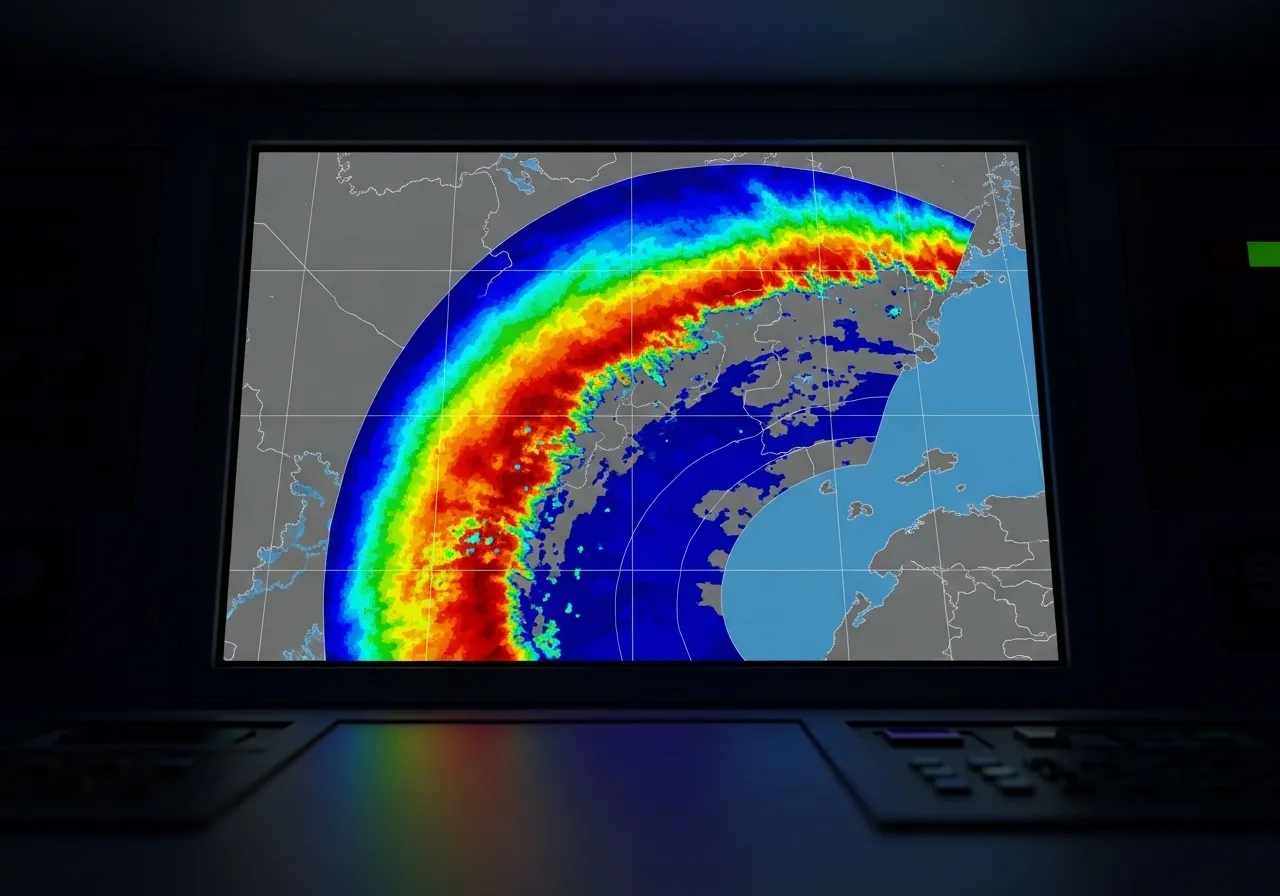

The most significant and unpredictable cause is weather. Adverse weather conditions account for the largest percentage of significant delays. This includes not only airport-specific weather like snow, ice, or fog, but also en-route weather such as major convective systems. A line of thunderstorms over the Midwest, for example, can force hundreds of flights to be rerouted, consuming airspace and fuel and creating a domino effect of delays nationwide. Winter storms can shut down an airport for hours, requiring extensive de-icing procedures that slow operations even after runways are cleared.

A second major factor is air traffic control (ATC) capacity and the national airspace system itself. The sky is not an open road; it is a structured system of highways, intersections, and altitudes managed by the FAA. When traffic volume exceeds what the system can handle in a specific sector, controllers must implement measures to slow the flow of aircraft. This is often done through a Ground Delay Program (GDP), a procedure where the FAA holds aircraft on the ground at their departure airport to manage arrival demand at a congested destination airport. This is a primary tool for preventing dangerous overcrowding in the air.

A simple worked example illustrates the GDP mechanism. Imagine Chicago O’Hare International Airport (ORD) can normally accept 100 arrivals per hour. A fast-moving thunderstorm reduces its capacity to only 50 arrivals per hour for a three-hour period. To prevent 150 extra planes from circling over Illinois, the FAA’s Air Traffic Control System Command Center will issue a GDP. A flight scheduled to depart from Los Angeles (LAX) for ORD might be held at the gate in LAX for an hour or more, waiting for a new arrival slot to open up in Chicago. This single weather event in one city creates departure delays thousands ofmiles away.

Airline-specific operational issues are another critical cause. These include maintenance problems that take an aircraft out of service unexpectedly, crew scheduling conflicts, and baggage loading delays. A flight crew timing out—reaching their maximum legally permissible work hours—can lead to a cancellation if a replacement crew is not immediately available. These carrier-related delays are often the most frustrating for passengers, as they can feel more preventable than acts of nature.

Finally, airport infrastructure itself is a limiting factor. The physical layout of an airport, including the number and spacing of its runways, the availability of gates, and the efficiency of its taxiways, dictates its maximum operational capacity. Many major U.S. airports were designed decades ago and now struggle to handle the volume and size of modern aircraft. San Francisco International Airport (SFO), for instance, has parallel runways that are too close together to be used for simultaneous landings in foggy conditions, drastically cutting its arrival rate and causing frequent delays.