Causes & Mechanisms: The Stories of 10 Abandoned Places

The reasons for a town’s demise are often complex, but for this category of ghost towns, a specific environmental hazard serves as the primary cause. A root cause analysis, a systematic method of problem-solving that aims to identify the fundamental cause of a fault or problem, reveals that these abandonments stem from both sudden disasters and slow-moving industrial crises. The mechanisms range from chemical contamination pathways in soil and water to radiological fallout blanketing entire regions.

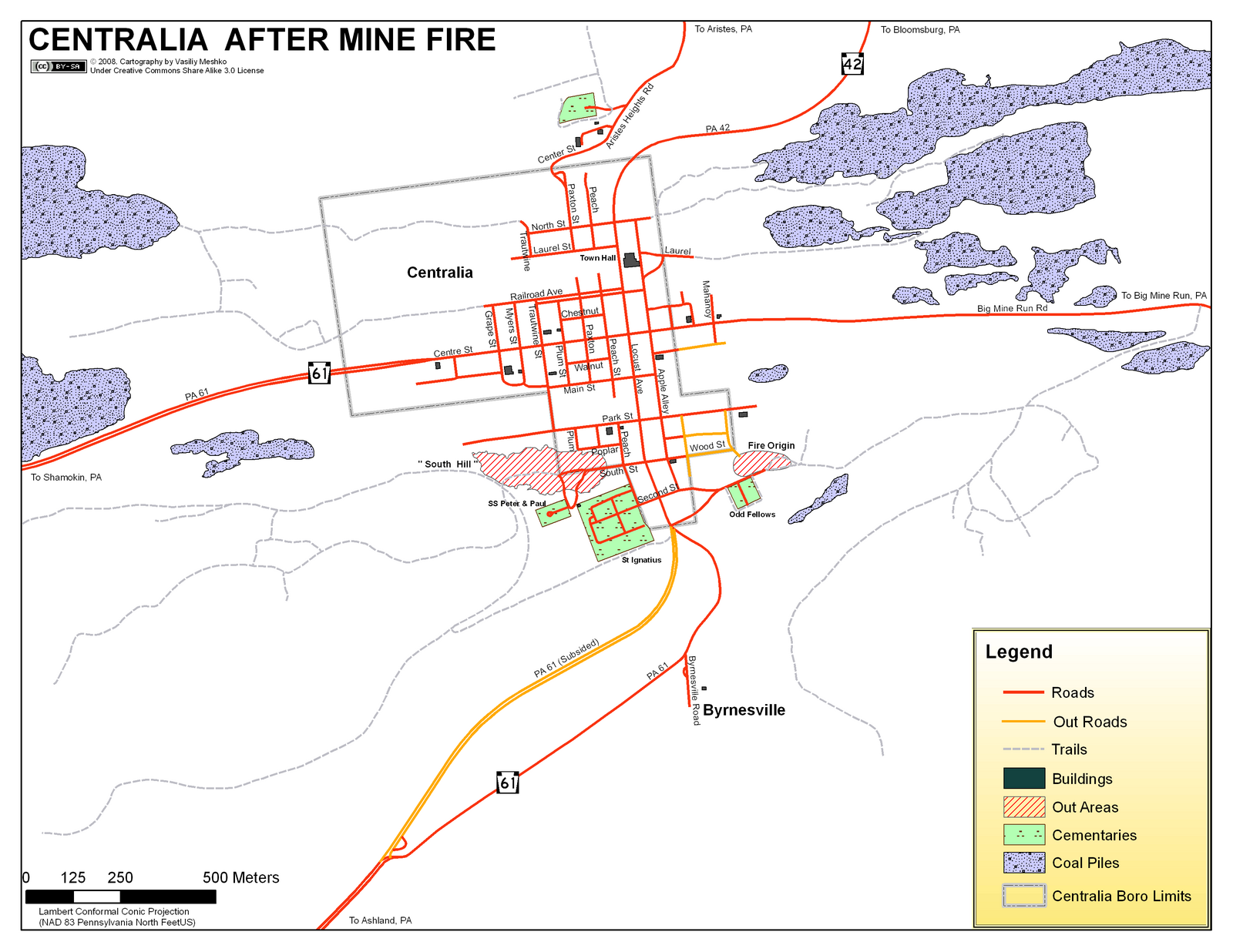

Centralia, Pennsylvania, USA: The Unquenchable Fire

Perhaps the most famous of America’s environmental ghost towns, the story of Centralia Pennsylvania is a stark illustration of a slow-motion disaster. The town sits atop rich veins of anthracite coal. In May 1962, a fire was intentionally set to burn trash in an abandoned strip-mine pit, a common practice at the time. This seemingly routine act had catastrophic consequences. The fire ignited an exposed coal seam, spreading into the vast network of abandoned mining tunnels beneath the town.

The mechanism of disaster was the fire’s subterranean, self-sustaining nature. Fueled by abundant coal and oxygen from the maze of tunnels, it could not be extinguished. Over years and then decades, the fire released toxic gases, including carbon monoxide and sulfur dioxide, which vented into basements and through fissures in the ground. The ground itself became unstable and hot, causing roads to buckle and sinkholes to open. Despite numerous and costly attempts to extinguish it, the fire continued its relentless march. The federal government ultimately allocated more than $42 million for a relocation program in the 1980s, leading to the town’s systematic demolition and abandonment. The fire still burns today and is expected to do so for over 250 more years.

Picher, Oklahoma, USA: A Superfund Catastrophe

Picher was once a national center for lead and zinc mining, vital to the American effort in both World Wars. However, this industrial prowess came at a staggering environmental cost. Decades of unrestricted mining left behind colossal piles of toxic mine waste, known as chat, which towered over the town. These chat piles contained high concentrations of heavy metals like lead, zinc, and cadmium.

The contamination pathways were numerous. Wind blew toxic dust from the chat piles across the town, settling on homes, playgrounds, and gardens. Rainwater leached heavy metals from the waste into the groundwater, contaminating local wells and the Tar Creek. The ground beneath Picher was a honeycomb of abandoned mine tunnels, making it dangerously unstable and prone to sudden collapse. In the 1990s, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) designated the area a Superfund site. Faced with pervasive lead poisoning among children and the imminent risk of subsidence, the government initiated a mandatory buyout, and the town was officially dissolved in 2013.

Pripyat, Ukraine: The Nuclear Shadow

Pripyat was a model Soviet city, built in 1970 to house the workers of the nearby Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant. On April 26, 1986, a catastrophic steam explosion and subsequent fire at the plant’s No. 4 reactor released massive quantities of radioactive isotopes into the atmosphere. This event, the worst nuclear disaster in history, rendered the surrounding area uninhabitable.

The mechanism of contamination was atmospheric deposition. A plume of radioactive material, including iodine-131, caesium-137, and strontium-90, was carried by wind across Ukraine, Belarus, and much of Europe. The immediate area around the plant received the highest concentrations. Within 36 hours of the explosion, the entire city of Pripyat, nearly 50,000 people, was evacuated. What was meant to be a temporary measure became permanent. Today, Pripyat sits at the center of the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone, a tightly controlled area where radiation levels remain too high for permanent human habitation.

Wittenoom, Western Australia: A Town of Blue Asbestos

From the 1930s to 1966, Wittenoom was Australia’s only supplier of blue asbestos (crocidolite), considered the most hazardous form of the mineral. The mining operations blanketed the town and the surrounding gorge in fine, airborne asbestos fibers. The tailings, or waste material from the mining, were even used to pave roads and fill schoolyards.

The health consequences were devastating. Inhalation of asbestos fibers leads to diseases like asbestosis, lung cancer, and mesothelioma, a rare and aggressive cancer. Even after the mine closed, the fibers remained deeply embedded in the soil and environment, posing a permanent risk. The government of Western Australia began a phased closure of the town in the 1970s, but some residents refused to leave. In 2007, the town was officially “de-gazetted,” its name removed from official maps and its services cut off, in a final effort to force its complete abandonment. It is now considered one of the most contaminated sites in the Southern Hemisphere.

Times Beach, Missouri, USA: Dioxin in the Dust

The story of Times Beach is a cautionary tale of improper waste disposal. In the early 1970s, the town hired a waste oil hauler, Russell Bliss, to spray its unpaved roads to control dust. Unbeknownst to the town, the oil Bliss used was mixed with toxic waste from a chemical plant that produced Agent Orange. This waste contained high levels of dioxin, one of the most potent carcinogens known.

The contamination was discovered in 1982 after the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) investigated unusual animal deaths in the area. Soil tests revealed dangerously high dioxin levels. That same year, a massive flood from the Meramec River submerged the town, further spreading the contaminated soil. In 1983, the EPA announced a federal buyout of every home and business. The entire town was evacuated by 1985, quarantined, and ultimately demolished. A massive incinerator was built on-site to burn over 265,000 tons of contaminated soil, a remediation project that took over a decade.

Gilman, Colorado, USA: A Mountain of Mining Waste

Perched on a cliffside in the Rocky Mountains, Gilman was a company town for the Eagle Mine, a major producer of zinc and lead for nearly a century. When the mine closed in 1984, the pumps that kept the tunnels dry were shut off. This allowed groundwater to flood the tunnels, where it became heavily contaminated with cadmium, copper, arsenic, lead, and zinc from the exposed ore.

This toxic water, a phenomenon known as acid mine drainage, began seeping out of the mountain and into the Eagle River, killing off most of the aquatic life for miles downstream. The EPA declared Gilman a Superfund site in 1986, and its remaining residents were evacuated. The town itself, along with vast amounts of mine tailings, remains a source of contamination, and the site is a focus of long-term remediation efforts to prevent further pollution of the river.

Fukushima Exclusion Zone, Japan: A Modern Nuclear Evacuation

On March 11, 2011, a magnitude 9.0 earthquake off the coast of Japan triggered a massive tsunami. The wave overwhelmed the sea walls of the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant, causing a station blackout and the failure of cooling systems. This led to nuclear meltdowns in three of the plant’s six reactors and the release of significant amounts of radioactive material.

Similar to Chernobyl, the primary mechanism of disaster was the atmospheric release of radioactive contaminants. The Japanese government established an escalating series of evacuation zones based on radiation levels, forcing the evacuation of over 150,000 residents from towns like Futaba and Ōkuma. While some areas have since been decontaminated and reopened, the most heavily affected zones remain closed. The disaster highlighted the vulnerability of critical infrastructure to compound natural hazards—in this case, an earthquake and a subsequent tsunami.

Aral, Kazakhstan: The Disappearing Sea

The port city of Aral was once a thriving fishing hub on the shores of the Aral Sea, which was, at the time, the fourth-largest lake in the world. In the 1960s, the Soviet Union initiated a massive agricultural project, diverting the two main rivers that fed the Aral Sea to irrigate vast cotton and rice fields in the desert.

The ecological mechanism was simple and devastating: the sea’s inflows were cut off, and it began to evaporate. By the 2000s, the Aral Sea had shrunk to less than 10% of its original size, splitting into smaller, hyper-saline lakes. The exposed seabed, contaminated with decades of agricultural pesticides and industrial runoff, became a toxic desert called the Aralkum. Windstorms picked up this contaminated dust, creating a public health crisis and destroying the regional climate. With the fish gone and the water miles away, the fishing industry collapsed, and the town of Aral became a landlocked ghost port, a symbol of large-scale ecological engineering gone wrong.

Pattonsburg, Missouri, USA: The Town That Moved

Pattonsburg’s story is one of natural disaster and proactive adaptation. Located in the floodplain of the Grand River, the town was historically vulnerable to flooding. This vulnerability became an existential threat during the Great Flood of 1993, a massive and prolonged flooding event across the Midwest. Pattonsburg was inundated for months, with most of its buildings destroyed or rendered structurally unsound.

Instead of rebuilding in the same vulnerable location, the residents made a collective decision. With assistance from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), they relocated the entire town to a new site on higher ground about three miles away. The original site, now known as “Old Pattonsburg,” was largely abandoned, its street grid a faint memory in a field of grass. It stands as a rare example of a community that chose organized retreat over a cycle of repeated disaster.

Salton Sea Communities, California, USA: An Ecological Collapse

In the 1950s, communities like Salton City and Bombay Beach were booming resorts on the shores of the Salton Sea, California’s largest lake. The sea itself was an accident, formed in 1905 when the Colorado River breached an irrigation canal. For decades, it thrived as an ecosystem. However, it had no natural outlet, and its water was supplied by agricultural runoff from nearby farms.

This runoff carried high levels of salt and nutrients from fertilizers. Over time, the salinity of the lake increased dramatically, while the nutrients caused massive algal blooms that depleted the water’s oxygen. This led to massive fish die-offs, which in turn decimated the populations of migratory birds that fed on them. The decaying organic matter produced a powerful stench, and the receding shoreline exposed a lakebed laden with toxic dust. The ecological collapse destroyed the tourism industry, and the communities withered, leaving behind decaying marinas and half-empty towns as a testament to a dying sea.